Life-saving research. World-shaping cultural exchange. A shared sense of civic participation. Creating pathways for adults to gain new skills. Equipping local employers with a ready workforce. The contributions colleges and universities make to American life are as varied as the institutions themselves. But from the smallest community college to the largest public university, one shared mission stands above the rest: particularly in the 21st century, going to college should be a springboard to a better life.

Success in that role depends primarily on two questions: Are we opening our doors to a wide range of students? And are those students leaving college with an education that puts them closer to the future they have dreamed of and worked for?

Whether colleges and universities can truthfully answer both of those questions in the affirmative should be among the most important metrics of a school’s impact. And yet, in our current system, institutions of higher education are often measured on and rewarded for metrics that have little to do with students and more to do with the institutions themselves.

Since its creation 50 years ago, the Carnegie Classifications system has become one of the most relied-upon lenses through which colleges view themselves and each other. Originally intended to support research and policy analysis, it has evolved to have a significant influence on higher education. For example, some funding agencies use it to make decisions about where to allocate resources, and through its use in the U.S. News and World Report’s “best colleges” rankings, the classifications have an enormous if indirect sway in how prospective students make quick decisions about which colleges are better than others. These unintended uses have had an undue impact on institutional behavior, and we want to reroute that influence to more squarely benefit learners.

With a better understanding of how these classifications are used, the American Council on Education and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching have been exploring how we can strengthen the classification system by incorporating a measure that examines how schools are serving students.

In next year’s release, as a complement to our revised Basic Classification structure, we are introducing a Social and Economic Mobility Classification. This new classification will identify schools that provide strong socio-economic mobility for students and offer insight into how a school compares to similar campuses. The new classification is intended to center students and drive institutional improvement that can increase access to higher education and improve outcomes.

To develop this new way of classifying schools, the methodology has to accomplish a couple of things. The first is to create groupings of similar institutions, likely connected to the Basic Classification, that would account for differences in areas like institutional missions, types of degrees granted, academic programs, instructional modalities, and availability of resources. By grouping similar schools, we aim to avoid the flawed conception of vastly different colleges being simply “better” or “worse” on a single continuum — that’s comparing apples to oranges and oranges to toaster ovens. We started working toward better groupings last fall with our revised approach to the Basic Classification (you can read more about that on our website).

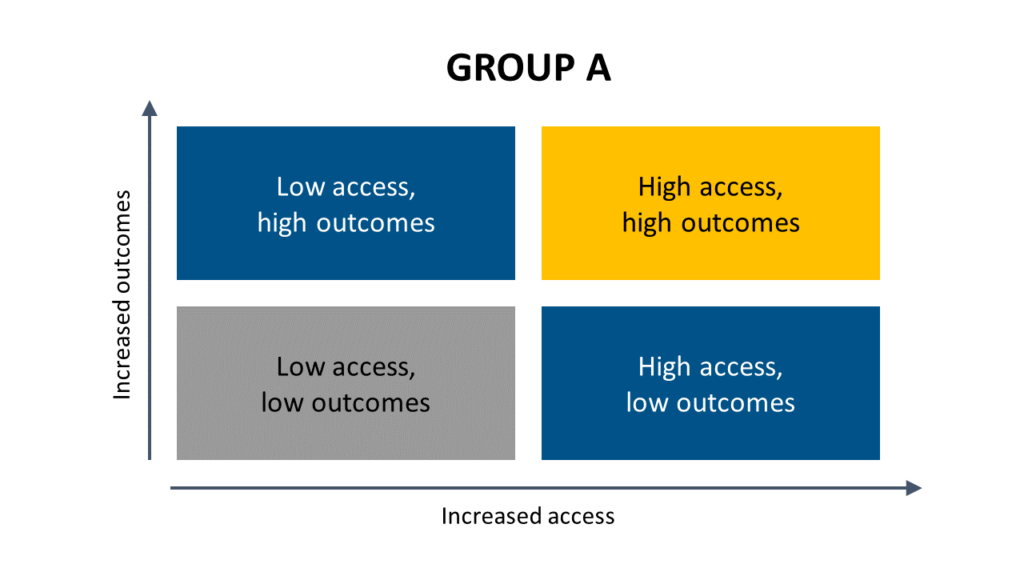

The second goal of our methodology is to determine the levels of access that schools provide to students and the economic success of those learners once they leave. We intend to measure these as separate ideas, recognizing that they are often conflated in other social/economic mobility models. By evaluating access and outcomes separately, we hope to better understand the multidimensional nature of social and economic mobility and categorize institutions in a way that can help inform the broader higher education field on how we can get every student into the world closer to the future they want and worked for. That is at the heart of what this classification is all about: strengthening our collective focus on student access as well as on outcomes.

We also intend to build into our approach some key context around the geographical area each institution is serving. A community college in New York City is very different than a community college in rural West Virginia when we consider the types of students they are serving and the workforce students face once they leave, but often their data are evaluated on the same scales. To make more meaningful comparisons, we plan to adjust for geographical context based on where students are from.

As we have worked with our Technical Review Panel, institutional leaders, and other experts to design this approach, we have had several principles in mind. One was that our approach should be relatively simple – and replicable – and we should use a few key metrics instead of many that are all highly correlated. Additionally, even within groups of similar schools, our goal is not to rank them against each other. We aren’t aiming to recreate some of the (laudable) algorithms that attempt to differentiate schools on a complex array of mobility metrics and then list them in a ranking. Instead, we want to illuminate how institutions are addressing these two fundamental goals and identify communities of similar institutions that can work together to improve. The resulting Carnegie Classification may look something like this.

There’s no perfect way to measure social and economic mobility, but the Carnegie Social and Economic Mobility Classification aims to be a more intentional way of measuring how colleges and universities are delivering on their fundamental promise of being socioeconomic engines that empower students to reach their fullest potential. And if we want to hold them accountable to that goal, we have to change the rules of the game so that winning rewards students. For us, that starts with reimagining the Carnegie Classifications.

As we continue to refine our methodology, we welcome any feedback that not only ensures we’re developing a system that truly prioritizes student access and outcomes, but also encourages institutions of higher education to work together to improve for the benefit of their students. Data shows that going onto postsecondary education is still a worthwhile step toward achieving the American dream – and we want to be part of the movement to strengthen that case across every college and university.